Experimental Use: Inspect your Invention, Strike it With Your Cane, and Examine its Condition

- July 17, 2018

- Article

Associated People

On July 13, 2018, the Federal Circuit issued an opinion in Polara Engineering v. Campbell Company, which has been noticed for its discussion of enhanced damages. However, the opinion is also notable for its discussion of experimental use to negate the statutory public use bar. In particular, it reminds us of a famous U.S. Supreme Court case on experimental use that is a staple of our patent law textbooks: City of Elizabeth v. American Nicholson Pavement Co. (U.S. 1877).

City of Elizabeth is memorable for its quoted testimony of a road toll-collector, Mr. Joseph L. Lang. Mr. Lang vividly described observing Mr. Nicholson’s (sometimes spelled “Nicolson”) almost daily inspection of an installed test section of his wooden road pavement invention: “he would examine the pavement, would often walk over it, cane in hand, striking it with his cane, and making particular examination of its condition. He asked me very often how people liked it, and asked me a great many questions about it. I have heard him say a number of times that this was his first experiment with this pavement, and he thought that it was wearing very well.” City of Elizabeth, 97 U.S. 126, 133-134. When reading this case for the first time in law school, I imagined an old Mr. Nicholson poking and prodding the test section of wooden pavement with his cane, pronouncing each day to Mr. Lang that he was satisfied with the pavement’s durability.

City of Elizabeth ultimately held that the installed test section of Mr. Nicholson’s wooden road pavement was a permissible experimental use, which does not constitute “a public use, within the meaning of the statute, so long as the inventor is engaged, in good faith, in testing its operation.” Id. 917 U.S. at 135. The Supreme Court noted that “the nature of a street pavement is such that it cannot be experimented upon satisfactorily except on a highway, which is always public.” Id., 917 U.S. at 134. So, even though the “public had the incidental use of the pavement,” the only way that Mr. Nicholson “could test it was to place a specimen of it in a public roadway. He did this at his own expense, and with the consent of the owners of the road…. He subjected it to such [experimental] use, in good faith, for the simple purpose of ascertaining whether it was what he claimed it to be.” Id., 917 U.S. at 136. The Supreme Court held that Mr. Nicholson did not gain any “undue advantage over the public”—and did not impermissibly extend his patent monopoly—by delaying the filing of a patent application due to this period of his experimental testing of the invention.

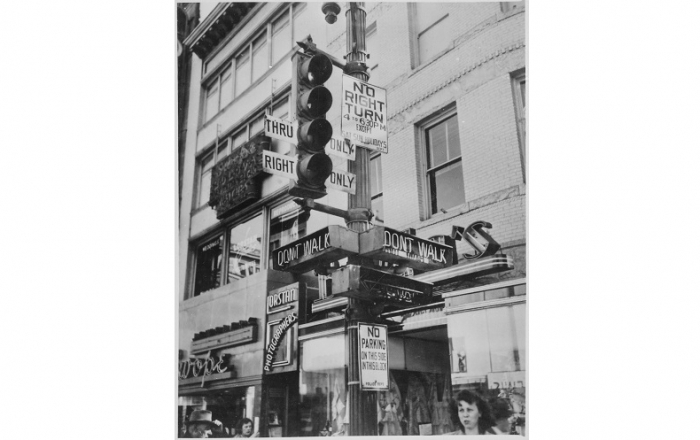

Fast-forward to Polara v. Campbell in 2018, in which plaintiff-appellee Polara is the owner of U.S. Patent No. 7,145,476, which “relates to a two-wire control system for push-button crosswalk stations for a traffic-light-controlled intersection with visual, audible, and tactile accessible signals.” Slip op. at 3. These crosswalk systems would alert pedestrians—whether visually impaired or not—when it is safe to cross the street at an intersection.

More than one year before filing the patent application that issued as the ’476 patent, Polara “tested prototypes that satisfied the limitations of the asserted claims” of the patent. Id. at 4. These prototypes were initially tested at a location close to Polara’s plant so that Polara could “monitor it daily during the test phase.” Id. Polara took “full responsibility for installing, maintaining”, and removing the prototypes. Id. Other prototypes were installed and similarly tested in other locations.

On appeal, defendant-appellant Campbell argued that the asserted claims of the ’476 patent “are invalid both for prior public use and over the prior art.” Id. at 10. The Federal Circuit disagreed, noting that:

“an inventor who seeks to perfect his discovery may conduct extensive testing without losing his right to obtain a patent for his invention—even if such testing occurs in the public eye.” Pfaff [v. Wells Elecs., Inc.], 525 U.S. [55,] 64 [U.S. 1998]. Proof of experimental use serves “as a negation of the statutory bars.” EZ Dock v. Schafer Sys., Inc., 276 F.3d 1347, 1352 (Fed. Cir. 2002). A use may be experimental if its purpose is: “(1) [to] test claimed features of the invention or (2) to determine whether an invention will work for its intended purpose—itself a requirement of patentability.” Clock Spring, L.P. v. Wrapmaster, Inc., 560 F.3d 1317, 1327 (Fed. Cir. 2009).” Id. at 11-12.

The Federal Circuit agreed “with Polara that substantial evidence supports the jury’s finding of experimental use that negates application of the public use bar.” Id. at 13. Particularly persuasive was testimony in the record that “Polara needed to test the claimed invention at actual crosswalks of different sizes and configurations and where the prototype would experience different weather conditions to ensure that the invention would work for its intended purpose,” that the testing was important for “a life safety device,” and that it was “imperative” because “public safety is [Polara’s] primary focus.” Id.

According to the Federal Circuit, the jury “could have properly based its finding of experimental use on the need for testing to ensure the durability and safety of the claimed” system. Id. The Federal Circuit analogized this to the facts of City of Elizabeth, in which “the Supreme Court held that testing an inventive pavement for “usefulness and durability” for six years on a public roadway constituted experimental use.” Id. Noting that the “factual situation here bears a striking similarity to the situation in City of Elizabeth,” the Federal Circuit explained that Polara’s invention:

relates to public safety in crossing the street, [and] the inventors could reasonably believe that they needed to ensure the invention’s durability and safety before being certain that it would work for its intended purpose. The trial testimony showed that durability and safety of the system could not be ascertained without it being subjected to use for a considerable period of time under different actual use conditions, e.g., different crosswalk sizes and configurations and different environments. Experimenting under actual use conditions necessitated that the testing occur at public intersections. Polara conducted this testing at its own expense and the jury heard testimony that supported finding that Polara was not commercially exploiting the invention during the … testing. Id. at 14-15.

In the end, the Federal Circuit reasoned that “[a]lthough the public use issue is close, given this mixed factual record, we cannot say that the jury’s finding of experimental use lacked substantial evidentiary support. To the extent [that defendant-appellant] Campbell invites us to reweigh the evidence, we decline the invitation.” Id. at 16.

So, even though “experimental use” is a possible avenue for negating the statutory public use bar, it is important to remember that it is not given the green light at every intersection.

Recent Publications

5 IP Rules to Know to Protect Your Business in the United States (article in French)

Coaching INPI Newsletter

Counseling & Strategic Advice

Counseling & Strategic Advice IP Transactions

IP Transactions Litigation

Litigation PTAB Proceedings

PTAB Proceedings Start-Up

Start-Up Technology Transfer

Technology Transfer Trademark & Designs

Trademark & Designs U.S. Patent Procurement (Application Drafting & Prosecution)

U.S. Patent Procurement (Application Drafting & Prosecution)